Editorial: County Supervisor Joan Honl wonders how to inform the public. We have her answer.

By Brandi Makuski

It’s time for municipal governments to make a solid policy against competing with the press.

It was during the Feb. 7 Library Board meeting that Portage Co. Supervisor Joan Honl (District 8) wondered aloud, “How will we inform the public about this change?”

Honl was referencing a change in library operating hours, one of several changes coming to the downtown branch of the Portage Co. Library following several instances of violence in or around the Main St. building over the past 18 months.

Honl’s right to be concerned, but the answer is so simple that it’s staring her right in the face. She just doesn’t realize it. Most people don’t.

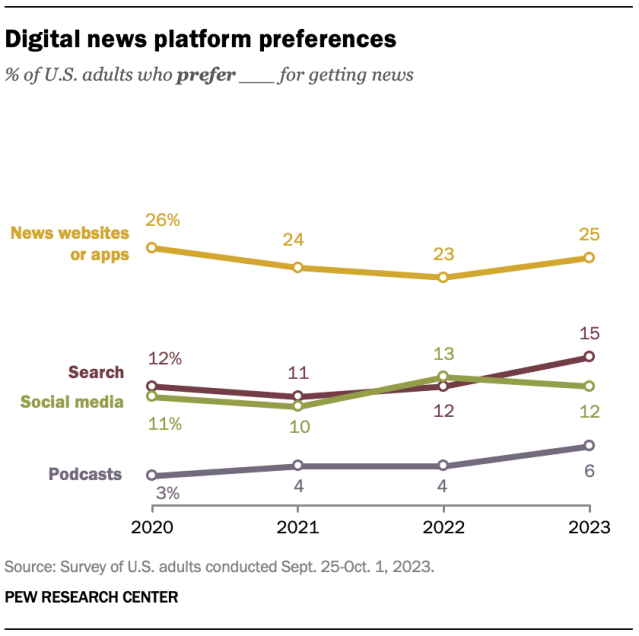

Even though it shouldn’t, social media plays a large role in news consumption for many. More than 80 percent of surveyed American adults said they get their news from social media “at least some of the time,” and 56 percent say they do so “often,” according to a new study from Pew Research Center.

The problem with this is that social media is a tool that all social media companies freely admit is very specifically tweaked to each individual’s online activity. It blurs the lines between what is news and what is not.

That alone is enough to prove it’s not a legitimate source of reliable information.

Its purpose is to entertain and advertise. And not just products: social media also advertises and/or encourages various lifestyles and belief systems. And despite the employment of “fact-checkers” (a practice discounted by fact-checkers themselves, according to the New York Times), social media, as a whole, does not practice independence, source vetting, or objectivity. It’s far from being free of influence, which is the key metric to any legitimate source of news.

Because of this, social media companies are facing a litany of lawsuits over mental health concerns, a recognized practice of preying on the weak, and encouraging unhealthy personal practices since the first whistleblower came forward in 2021.

The U.S. Surgeon General last May also issued a report on the negative impacts on mental health that stem from social media use.

Despite this, several municipal departments across Portage Co. — including county health and human services, law enforcement, fire/EMS, library, and parks — employ social media in direct competition with the local press, often skipping the press entirely in favor of a social media post. These posts range from merely informatory to promotion and advertising, and it’s often hard to tell which is which as a user is scrolling through a newsfeed.

A single post, even one based on fact, cannot be contextual and is just a tiny snippet of information. The hundreds (if not more) of Portage Co. social media users that these posts take away from local news outlets (and with them, our advertising revenue) may not recognize the difference between these posts and those from the true press.

Also despite this, school districts cling to social media platforms to share stories, some of which are formatted very much like a real news article, further blurring the lines between news and public relations to a user who’s looking for a quick fix of information. The local public school district even celebrates social media use, taking a monthly report of the “likes” and “shares” on its posts to the public, as if they held some value.

The 2023 Pew study referenced above does have some good news, though, showing that more people seek out news via news websites or apps, up slightly from 2022.

What the study doesn’t show is what value of a “like” or other engagement reaction from followers. But from practical experience, we can safely claim that a “like” helps boost a post’s visibility in the dastardly algorithm (a top-secret mathematical formula used by social media companies that determines when and where a post appears).

Plenty of studies are available on the topic from various “experts,” but none with Pew’s objectivity and methodology. However, those studies show that somewhere between 0.07 and 7 percent of a page’s followers actually ever see those posts, though it depends largely on which study you seek.

- A study from studio93.com says that the average number is 2.2 percent, while SocialInsiders Blog reports that the organic reach rate for Facebook is 5.90 percent in 2024 and that only about 7 percent of a page’s followers ever see a post on Instagram.

- However, according to Forbes.com, “organic social reach has been declining for years now, with research showing that just 0.07% of a Facebook page’s fans engage with the average organic post. Instagram and Twitter are also experiencing the same issue.”

Ever seen a post for the first time three days after it’s been posted? That’s the algorithm.

A 2022 study from statista.com shows that “a little over 50 percent of U.S. users’ news feed content on Facebook contained posts from friends and people they followed, whilst almost 17 percent of posts were completely unconnected to the user, meaning that this content was not related to their Facebook friends, or people, pages, nor groups that they followed. Moreover, the vast majority of news feed content did not have links attached.”

Also problematic is a 2022 survey from Pew shows that fewer Americans are closely following the news than they used to, with a particularly steep drop among people who are or lean Republican, “who also have become much less likely to trust information from national news organizations in recent years.”

A related study by The American Journalist shows that while most reporters identify as politically independent, journalists who say they are Democrats far outweigh those who claim to be Republican.

Returning to the original theme of this editorial, the facts we’ve laid out in this show how ineffective social media truly is.

Now, Honl is not to blame for the problems listed above. She’s probably not even aware that a problem exists (which is also concerning). Her words were simply the latest in public remarks made by a local elected official who seems to be grappling for an answer that’s been present the whole time. But she is part of a system that allows, and sometimes encourages, social media use by municipalities to continue.

The problems referenced above are clearly nuanced and overwhelmed with data.

But the solution is quite simple. Let the local press do its job.

We present you with a fine example of what this looks like in a social media world:

This post was made last October, with Vilas Co. law enforcement encouraging the public to seek follow-up information from local news outlets, and acknowledging that not everyone is on social media.

Now, I said the solution was simple, but I didn’t say it would be easy. The fact of the matter is, that without an independent news industry, democracy begins to crumble. And it begins at the local level.

The press can reach the largest single group of people interested in local news. And it’s time for municipal agencies to acknowledge this fact, and create media policies that discourage social media use for official purposes (outside of life-safety situations), and for school and community groups to conduct public education on the importance of news literacy.