Council members’ comments disappear from Facebook

By Brandi Makuski

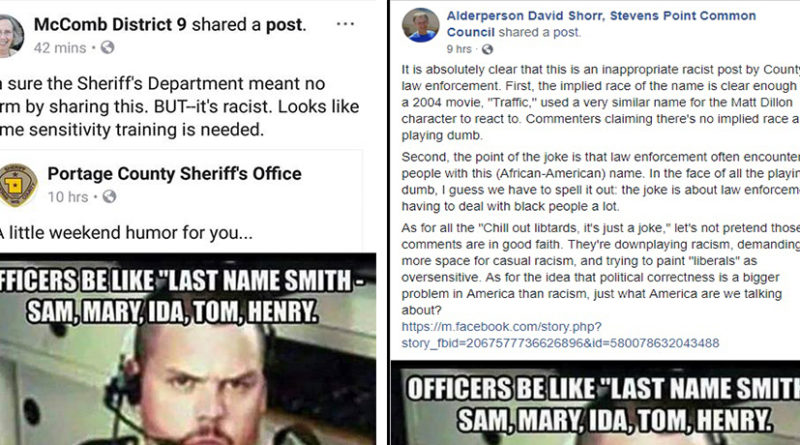

In the wake of some publications’ frenzied coverage on a recent social media post by the Portage Co. Sheriff’s Office, the public statements from two elected officials on the issue have disappeared from their respective office’s Facebook pages.

The Facebook post in question poked fun at the challenges dispatchers face when spelling uncommon names. The name “Tawneequa” was used in the meme placed on the community page for the PCSO Oct. 13, kicking off a fiery discussion over whether the post was racist.

Several local elected officials either referenced the post or shared it outright via their official social media accounts, denouncing it as “racist” or “offensive”, with many demanding an apology.

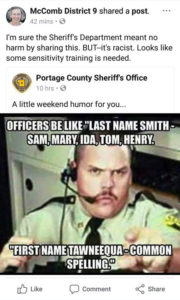

District 9 Councilwoman Mary McComb shared the post to her aldermanic page shortly before 3 p.m. on Oct. 13, adding her remarks about a need for local law enforcement to engage in sensitivity training.

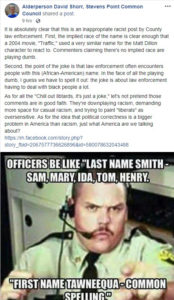

At about 11:40 p.m. on Saturday, Alderman David Shorr from District 2 also shared the post, adding three paragraphs declaring the name as African-American, saying, “Commenters claiming there’s no implied race are playing dumb.”

Shortly before noon on Oct. 14, both posts disappeared from the two alders’ pages, not long after the original post was removed from the sheriff’s office page. It was not immediately clear if the two were connected, and no clear answer was readily available in Facebook’s FAQ section. An email sent to Facebook corporate offices for clarification was not immediately answered.

A Wednesday phone call to Shorr seeking comment was not immediately returned. Following Monday night’s city council meeting, McComb said she wasn’t aware the post had been removed.

“I did not take it down,” she added. “I would never do that.”

Regardless, Mayor Mike Wiza said on Tuesday it’s still council members’ responsibility to keep track of their social media posts because they are considered public records under state law. The council was made aware of their responsibilities pertaining to social media, which includes acting as a custodian for records of their correspondence, during a May 22, 2017, aldermanic training workshop on the state’s open meeting and public record laws.

City Attorney Andrew Beveridge declined to comment on the issue.

During Beveridge’s training workshop last year, he underlined the need for council members to use caution while participating in social media, noting platforms like Facebook didn’t offer reliable methods for searching and archiving social media posts. He suggested council members keep track of their communications by copying and pasting them into a Word document, along with the times and dates of their posting.

“Your comments on social media are public records subject to discovery. Somebody could come to you and say, ‘I want to see all your social media posts for the last five months as they relate to your office’,” Beveridge said last May. “Any comment you put up online, anywhere, that relates to stuff going on in the city, is essentially a public record. It doesn’t matter if it’s posted through your aldermanic account, or a personal account, or anything else, it’s all the same.”

Under city ordinance 3.43, all communication and correspondence to and from city offices must be maintained for a period of seven years, though it does not specifically reference social media.

The ordinance essentially mirrors state statute 19.21, which also states anyone holding an office in state, county, school district, or municipal government is “the legal custodian of and shall safely keep and preserve” all public records pertaining to the office, to include records from their predecessor, for a minimum of seven years and only if they are considered obsolete.

Public records are also subject to inspection by a municipality’s historical society, which should be notified in writing at least 60 days in advance of their destruction, to determine if the records have any historical significance and should be preserved, the statute reads.

Anyone found in violation of the public records statute can face a fine of up to $2,000.