Editorial: What does “news” mean to young people?

By Brandi Makuski

In January, students at Pacelli High School completed their J Term projects: presentations to fellow classmates summarizing a nontraditional topic studied by small groups during a two-week period between Christmas and the start of the second semester.

Areas of study for the term change each year. In the past, students have studied the Florida Keys, the magic of Pixar, American Sign Language, small engines, or disaster preparedness, for one-quarter credit towards graduation. Each course was taught by an industry professional who gave students practical, hands-on experience in the area of study.

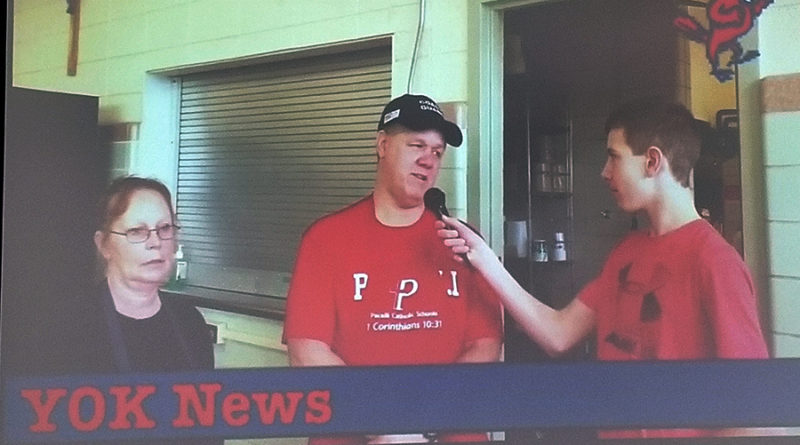

Except for one. This year, one class offered a look into the world of news reporting. The final presentation included a farcical, Ron Burgundy-esque video newscast about events taking place inside Pacelli. There was no instruction or guidance sought from a local working reporter or news anchor. The students didn’t even reference any local media outlets or the history of local news. The only source of information students used in their study of journalism was checkology.org, a website created by the News Literacy Project and Facebook Journalism Project.

Following the presentation, I asked one of the young men from the class why it hadn’t reached out to someone working in the field. He paused, shrugged, and said, “I guess we never thought about that.”

Earlier this year, Metro Wire staff met with officials in the Stevens Point Public School District for an informal, but candid, conversation about news consumer education. The problem, we suggested, was that young people today were missing out—and in a big way—in how they were finding and consuming news. Thanks in large part to social media, the way we take in information has changed, and fewer than 30 percent actually read beyond the headline of what they encounter online.

To prove the point, satirical news site the Science Post published the alarming headline, “Study: 70% of Facebook users only read the headline of science stories before commenting,” followed by three paragraphs of “lorem ipsum” text.

The post was shared on Facebook 46,000 times.

A generation ago, we grew up watching our parents thumb through newspapers. We learned what was worth caring about in our communities, and how to decipher the information presented. Educators would familiarize their students with newspapers in their classrooms. Students might be tasked with writing a letter to the editor, or taken on a tour of a local newsroom or television station. Learning about this institution was deemed important by school administrators.

That’s because they understood it, at least generally. Even in communities with competing print publications, the news consumption experience, and standards for publishing information were generally the same and could be summarized for a young reader. The same general format was being used by all news outlets: the most important stories were on a front page; the obituaries were in the same general place; the guidelines for attributing sources and verifying facts prior to publication were, basically, the same.

But those consistencies once relied upon by news consumers are changing quickly. As news publications are acquired by larger companies, and as local businesses move their advertising dollars away from traditional media, journalists lose their jobs.

About 71,000 positions were reduced to 31,000 between 2008 and 2017, according to Pew Research, and over 2,000 additional journalism jobs were slashed in the first two weeks of 2019 alone. Journalism cuts at media giant Gannett soon followed. Last week, the East Coast-based GateHouse Media announced it would consolidate 50 of its weekly newspapers into 18, having already eliminated 200 jobs.

There are fewer people working in the industry across the nation, which means fewer eyes on the process and the final product. It means shortcuts. Originally-written stories are replaced by canned content and advertorial-like press releases without a staff byline. Sometimes it means mistakes are made, or important questions for a story go unasked. In some instances, it can mean biases go unchecked—creating a breeding ground for their growth, which is contraindicative of news reporting in the first place.

It may be an oversimplification, but it’s no wonder the class at Pacelli made light of the news reporting profession. It’s fast-becoming an easy profession to dismiss, and it’s difficult to fill open positions due to the financial instability of the industry.

There’s no easy solution to this problem, which is nuanced, but ignoring it definitely isn’t the answer. School districts, business sectors, municipal and public safety agencies—all should receive a frank education on the state of news media, and be taught how to navigate it, just as was done before the invention of the internet.

Readers, too, play a large role in the future of news, because they decide how relevant local news is inside their own homes, and they can choose where to spend their subscription dollars.

Those subscription dollars are more precious than ever—so it’s in a reporter’s best interest to do their jobs well, and the best measure of that performance is the opinion of the reader.

It’s a problem we need to address swiftly in our families, our schools, and our institutions, or the Fourth Estate may very well become irrelevant or unsustainable, and J Term classes in the future may be studying about it in the past tense.

Send your open letters to [email protected]